09 Giu THE VOICELESS CREATURE OF GEORGI GOSPODINOV

THE VOICELESS CREATURE by GEORGI GOSPODINOV

interview by Erika Nannini

translated by Sara Manuela Cacioppo

Alberto Burri, Cretto, concrete, 1984-2015; 150×35000×28000 cm

The magazine which I work for is called Morel, voci dall’isola and deals with the correlation between literature and images. Your novel Fisica della malinconia (The Physics of Sorrow) is, in my opinion, a visionary novel and has a strong evocative power. According to you, can we call you a writer whose images anticipate what you will write?

Roma: Voland; 2013; 335 p.

I would rather say yes. I cannot write about a thing if I cannot imagine it. Sometimes it is important for me to know even how it smells. Actually, “The Physics of Sorrow” was born out of one particular scene, a childhood memory. I was 7-year-old, alone at the only room of our rented home. It was getting dark, my parents were not coming yet. I sat facing the window with my back to the darkening room. The window was low, at the street level, we used to live at the ground floor. And I was looking at the people passing by, only the lower half of them, only legs and shoes, and I was trying to imagine the upper part. I was afraid and feeling forgotten. Later, another creature came into that picture – The Minotaur, the loneliest one in the mythology, another little boy abandoned in the dark. And “The Physics of Sorrow” was born out of the blending of those two images.

The next issue of the magazine will be dedicated to the myth of Ariadne and in your novel I found interesting your point of view on the figure of the Minotaur. It is poignant and very far from the idea of the monster we are used to know. We often forget that anyone, in the course of his life, has been at least for once defenceless, there is no monster that has not also been his mother’s little one. In order to remember it, do we need to make peace with the monster inside us?

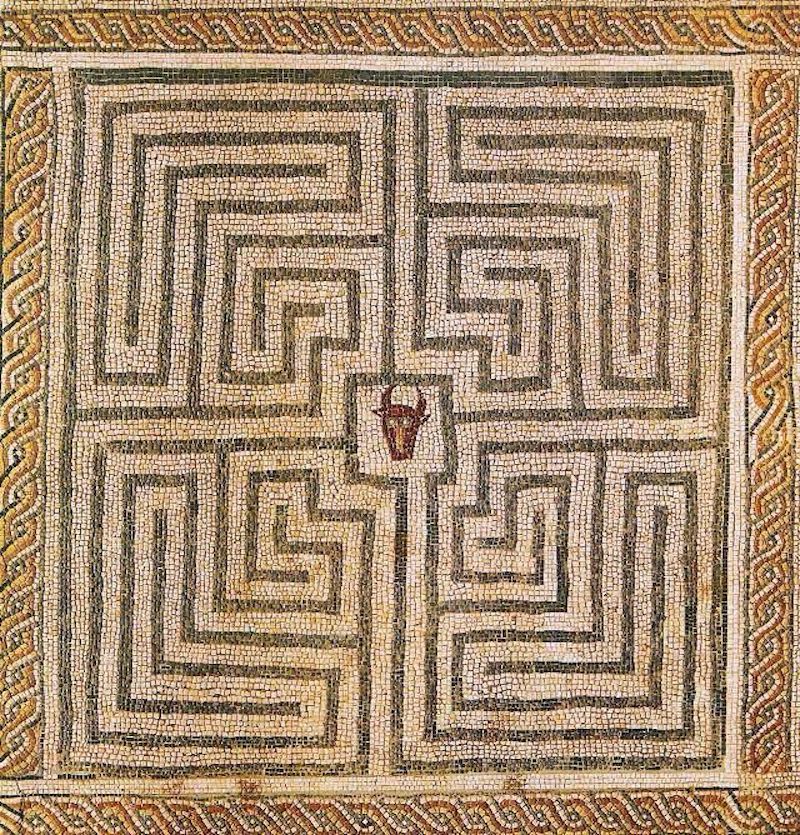

Pasifae with the newborn Minotaur on a red-figure “kylix” dating back to 330 BC

I have read everything that I managed to find about the Minotaur, from the ancient classical authors till today. There is no breakthrough concerning the image of the monster. But if we read the myth carefully, with a drop of empathy, we will see that it is about an abandoned child, a 2-3-year-old boy with a bull’s head locked in the basement of king Minos. There is one preserved vase painting (found in today’s Italy, by the way), it is on the cover of the novel, and it shows Pasiphae holding the little baby-Minotaur. Apart from the little bull’s head, it looks like Mary with the little Jesus. Ultimately, this is what literature is doing. Where we used to see a Minotaur, now we can see a person scared to death, an abandoned child. In fact, the whole myth tries to cover up that sin turning the victim into a monster. Going back to your question, yes, of course, at some point we understand that we are at the same time the labyrinth and the monster in it. Most often it is a child that we had once abandoned. That is why in one of the possible endings of the novel, Theseus and the Minotaur are talking and walking out of the labyrinth together. Sometimes we just have to restore the conversation with the child that we have fabricated as a monster.

In classical mythology, as you point out in the novel, the Minotaur never speaks, the bull’s head prevents him from doing so, and in Fisica della malinconia (The Physics of Sorrow), perhaps for the first time ever, he does the only thing he can really do: moo. This detail made me think of a curious thing, which is that in mythology we have the Sphinx and the Centaur, but in both cases they can speak because it is only their body that takes the form of a beast, while their head remains human. Do you think it was important, at the origin of this myth, that the Minotaur could not defend himself or have a different idea from the one that men attributed to him?

Yes, and that is why the Minotaur is the most tragic figure in the whole mythology. To be deprived of personal voice and story is the greatest punishment. In a mythology in which everything, living or dead, speaks, the Minotaur has no voice which means no story. That is the lowest level a living creature could reach. In a way this is also an allegory of the human history till today. Both mythology and propaganda know – if you want to deprive somebody of their human nature, you should deprive them of their story and voice. And that person turns into nobody. And vice versa, if you want to resurrect somebody, you should give them the right to have a voice and a story. The other thread in this character is connected with this ‘Mooo’ which in all human and animal languages (this is my interpretation) is based on the word for Mother.

Roman mosaic

In a passage of the novel you wrote that it is easy to empathise with Icarus and be on side of Theseus or Ariadne, on the contrary nobody empathises with the Minotaur. Is it difficult to empathise the Minotaur because he is a monster or because he is alone in a society where those who are alone are always wrong?

The Minotaur is the absolute Other, he is the one in the dark whose face we cannot see clearly. And if we see it, we would get terrified even more because there is no face, there is a muffle. That he is deprived of speech makes the things even worse, it makes him even scarier, you cannot negotiate with him. And the scariest thing, the unforgivable which we do not dare say is that in fact we have caused this to him. Pasiphae’s adultery with the bull, Minos’s shame, his idea to lock in the dark this child of sin. The Minotaur is a child of our own sins. He is the concealed, unspoken sin we decided to separate from ourselves. We lock such things in the basement of our subconscious. To be able to feel empathy you must see a child in this body. To be able to see the abandoned child, you must overcome the feelings of fear and disgust to your own self as part of the same kin that has done this unjustice… Thus we reach an earlier question – you must begin the conversation with your own Minotaur, the Minotaur within you.

In a passage of the novel your protagonist declares that he hates Ariadne because she betrayed the Minotaur. In fact, even though they have the same blood because they are brother and sister, she sacrifices him to help the man she fell in love with. Supporting this point of view, we could consider her action only as one of the many betrayals that she has committed, for example by fleeing with Theseus she has also abandoned and betrayed her homeland and her King, her father. However, these considerations do not concern the character of the protagonist and the sense of abandonment and loss that is visible throughout the novel. But, what is the writer’s point of view on the figure of Ariadne?

Let’s not forget that Ariadne (at least in Ovid’s version of the myth, in his Heroides) is the only one who calls the monster “my brother, the Minotaur” and thus grants him human status. She is saying this exactly in her letter to Theseus, after he has betrayed her, too. This also got into the novel. Otherwise, Ariadne’s crime is a crime of love. But the most important for me in this novel was Ariadne’s thread. It was important even technically, as a way to connect the different stories in time. The narrator’s voice and his ‘super-empathy’ are supposed to have the function of such a thread. Because of the different point of view to the myth, Ariadne appears simply as the sister of the Minotaur. And she gives the idea of the thread through the book’s labyrinth so that the readers wouldn’t get lost in the corridors.

Roma: Voland; 2020; 160 p.

I was thinking maybe you could tell me a little bit more about your new book of supershort stories Tutti i nostri corpi (All our Bodies), which has just been published in Italy thanks to Daniela Di Sora, a much-loved woman, and Voland, a formidable publishing house.

This is a book with 103 ultra-short stories, the shortest one is of three words, the longest one is three pages. The book came out in the first days after the quarantine and has already received a very good response. This is extremely inspiring, people have kept their story hunger after what they have been through. What more could we wish for. There was a small online reading and Daniela read a very innocent story from the book, about preparing an evening meal, which ended with the sentence: “We were not created to have dinner alone.” Suddenly there was such an intense silence. And you understand that after all we have been through, our stories will not be innocent any more. Yet again, after all this, the book sounds in fact very lucidly, at least according to the Italian critics.

Georgi Gospodinov (Bulgarian: Георги Господинов; born January 7, 1968 in Yambol) is a writer, poet and playwright based in Sofia, Bulgaria. One of the most translated Bulgarian authors after 1989, he has four poetry books awarded with national literary prizes. First of them, Lapidarium (1992), won the National Debut Prize. Volumes of his selected poetry came out in German, Portuguese, Czech, Macedonian. Gospodinov became internationally known by his Natural novel, which was published in 21 languages, including English, German, French, Spanish, Italian, etc. The New Yorker described it as an “anarchic, experimental debut”, according to The Guardian, it is “both earthy and intellectual”, Le Courrier (Geneve) calls it “a machine for stories.”. In Italy his novels are published by Voland publishing house.

No Comments